Moe Asch wanted to record everything. So when he started Folkways Records in 1949, he didn't act like a major label record executive—he acted like an archivist. He didn't charge musicians to use his recording studio—you could just walk in. His records didn't come in glossy packaging—they came in rough cardboard and plastic sleeves with photocopied liner notes. And he wasn't just interested in folk music, or even "music" at all. He wanted to have recordings of animals and car races and steam locomotives and kids singing at summer camp:

These kinds of sounds—what we might now think of as sound effects or soundscapes or ambiences—were actually not hard to find on vinyl in the 1950s. Thanks to the development of hi-fi stereo systems and magnetic tape recorders, there was a boom in the marketplace for recordings of...almost anything. These recordings were often packaged into what were called "demonstration discs," compilations of field recordings, mechanical noises, and/or bombastic pieces of classical music (lots of Wagner, obviously) meant to push your home stereo to its limits. (The classic article on this, which highlights the masculine nature of stereo obsession, is Kier Keightley's "'Turn It down!' She Shrieked: Gender, Domestic Space, and High Fidelity, 1948--59.") Here's a good example of a demonstration record, produced by London FFS in 1958:

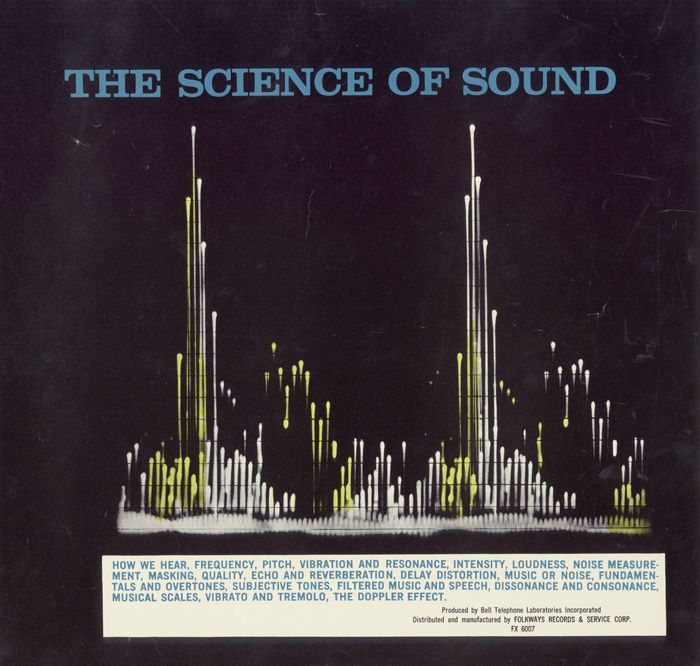

Folkways contributed to this genre but also reinvented it. Asch grouped recordings like this into what he called the "Science Series," which was both a literal and and aspirational title. Some recordings were quite scientific, others were more, shall we say, creative in their approach, yet were passed off as having scientific legitimacy. The most famous of these is certainly Sounds of a Tropical Rain Forest in America, which played in the American Museum of Natural History in the early 1950s to accompany an exhibit on a Peruvian tribe—even though it did not include a single recording made in Peru. I have written about this record and its history in Folkways Magazine, where I argued that by editing nature recordings in this tape collage style, and eventually removing the narrators, Asch created what is in many ways the template for "nature sound records" from the 1960s through today. And I still think that's the case.

I have been fascinated with the Folkways Science Series for years, so needless to say it is a pleasure when I find someone else who wants to talk about it. One of those people is Brian Hirsch, a neighbor of mine who I met in a nearby park—me out for a walk with my toddler and him with his Pomeranian. (If there is an upside to a global pandemic, it might be getting to meet all of your neighbors with dogs and kids.) I think I was wearing my Folkways hat and Brian happens to host a folk radio show on a community radio station. He has been involved in music scenes for a long time as a player, booker, and live sound engineer.

So we struck up a conversation. As is often the case, I had to explain that my interest in Folkways actually had very little to do with folk music. Brian nodded politely, because he is a decent person, but he also seemed genuinely interested. He asked me to be a guest on his radio show, to talk about the non-folk music of Folkways records.

So I did that. I talked about some of my favorites from the series, and Brian edited in example sound clips. You can hear the audio right here, but if you want to do some further sonic exploration, here are Spotify links to the records we talked about:

- Charles Bogert, Sounds of North American Frogs

- Sound Patterns

- Tony Schwartz, New York 19

- John C. Lilly, Sounds and Ultrasounds of the Bottle-Nose Dolphin

- Sounds of New Music

- Sounds of a Tropical Rain Forest in America, and another link to the article I wrote about this record.

Let me know what you think—and if you have any old and weird environmental records or demonstration discs lying around. I'm always up for hearing and learning more.