The above audio is a "remix" of a 1979 version of Roger Payne's Songs of the Humpback Whale that was pressed onto a "Flexi disc" and accompanied an essay he wrote in National Geographic magazine. I edited excerpts from that recording with additional whale songs, sound effects, and music from Blue Dot Sessions. This week's newsletter is a deep dive (that's right) into whale songs and other other underwater recordings.

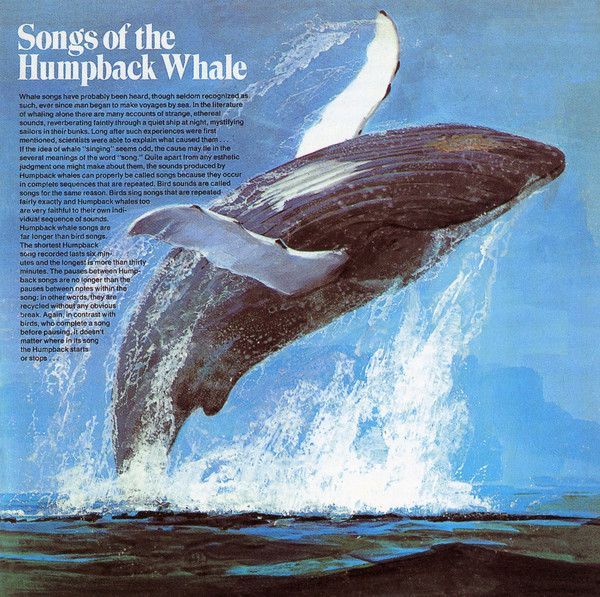

2020 marks the 50th anniversary of Songs of the Humpback Whale, an album that gives listeners exactly what the title promises: underwater recordings of whales. It was an unlikely hit, especially on college campuses, and brought the haunting and beautiful cries of these ocean mammals into living rooms and dorm rooms across the country. To this day, even though I have heard it dozens of time, it's still hard to believe that the sounds are real.

There are many fascinating stories around Songs, but I have always been interested in how this record—and other recordings made with underwater microphones called hydrophones—completely shattered the notion that the sea was silent. Renowned oceanographer Jacques Cousteau made that idea his entire brand; his landmark 1952 underwater documentary was called Le Monde du Silence, The Silent World.

But now there was strong evidence otherwise. In the middle of the twentieth century, the ocean went from being silent to being a vast switchboard or concert hall, where important communications and otherworldly music reverberated just outside of human earshot.

The first audible hints of this revelation can be traced back to the 1940s. According to Rachel Carson's The Sea Around Us—winner of the 1952 National Book Award for nonfiction—the United States Navy set up a network of hydrophones in the Chesapeake Bay to detect submarines. But in the spring of 1942, that system was overwhelmed and rendered useless by a sound that hydrophone operators described as "a pneumatic drill tearing up pavement." Soon the sailors realized that the sounds belonged to members of the appropriately named croaker family of fish.

These sounds remained a military secret and were largely unknown to the public for a decade, but shortly after Carson's written account of what a hydrophone could capture, Folkways Records released the unofficial soundtrack: Sounds of the Sea Vol. 1: Underwater Sounds of Natural Origin, recorded by the Naval Research Laboratory. The sounds had gone public, and they were, in a word, surprising.

In the liner notes for the album, C.W. Coates writes, "to think of fishes making noises, holding conversations, so to speak, warning each other or courting each other, as we think of birds singing to each other, is an idea which seems as strange as it well can be...fishes would appear to be among the most silent of all inhabitants of the globe."

So Jacques Cousteau was pissed. In his 1953 book, also called The Silent World, he railed against these recordings as fundamentally unnatural, not representative of the way a human being actually experiences the underwater soundscape:

"The sea is a most silent world. I say this deliberately on long accumulated evidence and aware that wide publicity has recently been made on the noises of the sea. Hydrophones have recorded clamors that have been sold as phonographic curiosa, but the recordings have been grossly amplified. It is not the reality of the sea as we know it with naked ears. There are noises underwater, very interesting ones that the sea transmits exceptionally well, but divers do not hear boiler factories."

Unfortunately for Cousteau, this ship had already sailed. Much of the record-buying public seemed less interested in how these recorded sounds corroborated with human experience than how they corroborated anecdotal, fictional, and mythological stories about hearing odd sounds at sea. For all of their crackle and static, hydrophone recordings deepened the mysteries of ocean sounds that stretch as far back as Homer's sirens. One reviewer wrote, "Recordings of underwater sounds of biological origin would have little meaning if we were content to file them simply as a document of science. Yet when related to the past, they stand for more than this: they stamp with absolute authenticity some of the wildest dreams of our ancestors; they corroborate our prophets; they stand back of our poets."

This sea change (did it!) in our cultural understanding of ocean sounds corresponded with an even broader change in how "nature" records were packaged and sold at this time. Albums like Sounds of the Sea reflect a 1950s "scientific" paradigm, where the specifics of the recordings were extremely important. Check out this track listing, filled with species names, depths, and locations:

But by the end of the 1960s, that model had been almost wholly replaced by things like this:

At the bottom of that image you'll see, "Side 1: Psychologically Ultimate Seashore." One track, no location information, very few details. This was the Environments series, which collapsed all nature sounds into representative and generic samples: seashore, rainforest, waterfall. The American environmental movement of the 1960s, driven mad by jet engine noise and armed with the new language of ecology, redefined "noise" as a kind of pollution and "quiet" as a natural resource and even a human right. The result was a notion of nature that was both ecological but also profoundly individual to the point of being interior and psychological. Also, as it turned out, records like this sounded even better if you were on drugs.

This was the cultural moment that Songs of the Humpback Whale emerged into, and was probably the reason why it the best-selling album over the 1970 Christmas season at the Harvard Co-op. But even though the album was part of this new psyched-out nature record moment, its origins were still in naval research and the biological sciences. Though the album is widely credited to American biologist Roger Payne, most of the recordings were done by Navy hydrophone technician Frank Watlington off the coast of Bermuda. Depending on who is telling the story, the recordings were made sometime between 1958 and 1964 and shared with Roger Payne and his wife Katy sometime between 1964 and 1966. Katy and Roger were traveling to Bermuda to conduct their own research and recordings of whale populations, which at this time were in severe decline due to commercial whaling. In a story that Katy has told, Watlington kept these recordings private and shared them with the Paynes specifically to "go save the whales." And, in many ways, they did.

Even if Songs of the Humpback Whale was good to get high to, it was framed specifically as a way to raise awareness to the plight of the whales and other marine mammals. The music and the message almost immediately took hold in the cultural imagination, especially among musicians. Within months of its release in 1970, selections from Songs of a Humpback Whale had been incorporated into "And God Created Great Whales," a composition by Alan Hovaness, and "Farewell to Tarwathie," a Celtic whaling ballad recorded by folk singer Judy Collins. In 1977, the whale songs actually left earth as part of the Voyager Golden Record. And in 1978, Kate Bush used twenty seconds of Payne's recordings to open her debut album, The Kick Inside.

But for all of their environmental rootedness, the songs of the humpback whale remained to most ears decidedly otherworldly. Songs of the Humpback Whale was almost universally compared to two things: the sounds of electronic music and the sounds of outer space. One reviewer noted that whale songs sounded "so completely otherworldly that they might have been radioed back to earth from a Soviet rocket probe that landed on Venus." Another reviewer put it more succinctly: "if you didn't know better you would think they the sounds were electronic." Much like the earlier hydrophone records before them, whale song records were not—could not—be understood in reference to the way they sound to human ears out in the world; they could only be understood in relation to other kinds of recorded sound and music. Unlike Cousteau, few of us have access to the undersea "silent world." Instead, we dwell on the surface, where underwater sounds remain a strange and beautiful and unknowable music.

Note: Much of this material is repurposed from a presentation I gave in 2014 at the IASPM-US academic music conference.