As a parent, I read a lot of children's books. And a lot of children's books are about animals, sounds, or animal sounds. But one particular book came home in a recent library haul that really surprised and delighted me: A Fox Found a Box, by Ged Adamson. In this book, a cute lil' fox finds a portable radio in the snow, turns it on, and soon they and all their forest friends experience the joy of music. Eventually, the radio runs out of batteries, leaving the animals in silence. Then—and only then—does the animal crew come to appreciate the sounds of nature all around them.

I loved the book and its themes so much that I wrote to Ged to see if he wanted to chat. Not only did he say yes, he sent me some of the earliest sketches he made for the book, some finished illustrations that didn't make the cut, and some lovely scans of the final pages. He generously talked to me about his process, including how he and his editorial team worked to shape the story.

We'll get to that conversation in a minute, but first, I just want to say why I found this book so satisfying. For a long time, there has been a subtle, even subconscious way of thinking in certain communities of musicians, artists, and intellectuals that divides all sounds into two categories: "natural" sounds and everything else. (This split has a direct corollary in the distinction between "nature" and "culture" that Bill Cronon famously dismantled 30 years ago in "The Trouble with Wilderness.") The "soundscape," a term that emerged in the 1970s, was an idea just as romantic as the "landscape": a vast, beautiful place completely empty of humans.

The problem with this romantic view of nature and sound is that the very notions of soundscape and landscape are cultural. The ability to study soundscapes in a systematic way was made possible through microphones and portable magnetic tape recorders. And the people who were most interested in soundscapes were people who were steeped in Western experimental music traditions. In other words, early soundscape advocates were already thinking of the sounds of the natural world through the lens of Western musical traditions.

One key figure in this history is Murray Schafer, a Canadian composer who is sometimes credited as coining the term "soundscape." His book, The Soundscape: The Tuning of the World, reflects a particular kind of fantasy wherein the world is an instrument that can be played or an orchestra in need of a conductor. (For more on Shafer's complex legacy, see the two-part series that Mack Hagood did on Phantom Power: part 1 and part 2.)

Many other advocates and artists in the world of field recording come from a similarly musical background. Chris Watson, the most aesthetically interesting field recordist working today, got his start in the experimental band Cabaret Voltaire. And Bernie Krause, a field recordist who has written extensively about "soundscape ecology" (an attempt to make soundscape-style thinking more scientific) was a part of the synth / psych-rock band Beaver & Krause.

So, to state the obvious: the ideas we carry around about "natural" sounds are shaped by human culture through and through — by how they are recorded, edited, packaged, studied, disseminated, discussed. As Jonathan Sterne has argued, even the definition of "sound" is tied to humanness, since it is the limits of our eardrums that define sound as a separate category from the many other vibrations around us.

But that, of course, does not make natural sounds any less beautiful, or valuable, or meaningful. It means that caring for these resources is also a cultural concern. Appreciating any sound is a learned and often communal experience. And that is what Ged Adamson gets exactly right in A Fox Found a Box. The fact that these animals hear music first, and then come to appreciate the environmental sounds around them, I think gives us all a little lesson in how to listen.

A Fox Found a Box

Ged Adamson was a musician before he was a children's book illustrator. He was largely self-taught, and as a teenager he told me he was in "really, really terrible bands." In his 20s, he was signed to a publishing deal but never broke out as an artist. Instead, he ended up writing music for commercials and video projects, which inspired him to get into visual art and illustration.

I had a chat with Ged (pronounced like Jed) over Zoom from his flat in London. We had a really thoughtful conversation about the origins of his idea for this story, how books develop and change in the editorial process, and what it means to slow down and appreciate our environments: urban, rural, and otherwise.

Here are Ged's drawings and edited excerpts from our conversation.

Craig: Can you tell me how the idea for A Fox Found a Box first started?

Ged: I think the first spark of the idea was seeing on TV that thing where a fox jumps into the snow and they're looking for things to eat. And I just thought that is really cool.

And I just had this idea, what if Fox jumps in and uncovers a radio?

Before I wrote books and illustrated, I used to do music as a job and I've just always been interested in music and sound, and so this was an opportunity to do something with that idea.

I just really liked the idea of the fox kind of being stalled by this noise, you know: what's that? And then what happens when that goes away?

I love the sketches of the radios. Did you have a particular radio in mind from your past?

In our house, when I was a kid, we had just a really, really old radio. And the reason we had an old radio was because my mom and dad just weren't big radio listeners. So I was thinking of that — but it was just an amalgamation of different old-school kind of things.

The thing about the radio that me and the editor would discuss is if the kid's gonna know what a radio is. Because it's almost a sort of obsolete thing, isn't it?

But if you are a kid, you're gonna listen to devices. Not radios, but in the end we said, well, it doesn't really matter if little kids don't really know what that is. They will know that there are speakers you have around the house that sound will come out of.

So nowhere in the book do you call it a radio?

Right.

The book has a few pages where the animals listen to music and it gives them different feelings: it felt nice, it felt dreamy, it made them wanna rock and roll. Does music give you those feelings?

What's crazy and weird and beautiful about music is that it doesn't have to be like big orchestral, classical film music to make you feel something.

I really love pop music, and I can almost be brought to tears by a really great pop song. You know, it doesn't have to be sad. It just makes you so emotional, and you can't really explain it.

I mean, you can more explain it when it's like the Adagio for Strings thing and it's that massive emotional thing. But I don't know why, a really beautifully made pop song just gives me…this kind of emotional response that's almost overwhelming.

Then, of course, the radio's batteries run out, and that makes the animals pretty sad. It's like taking a toy away from a kid.

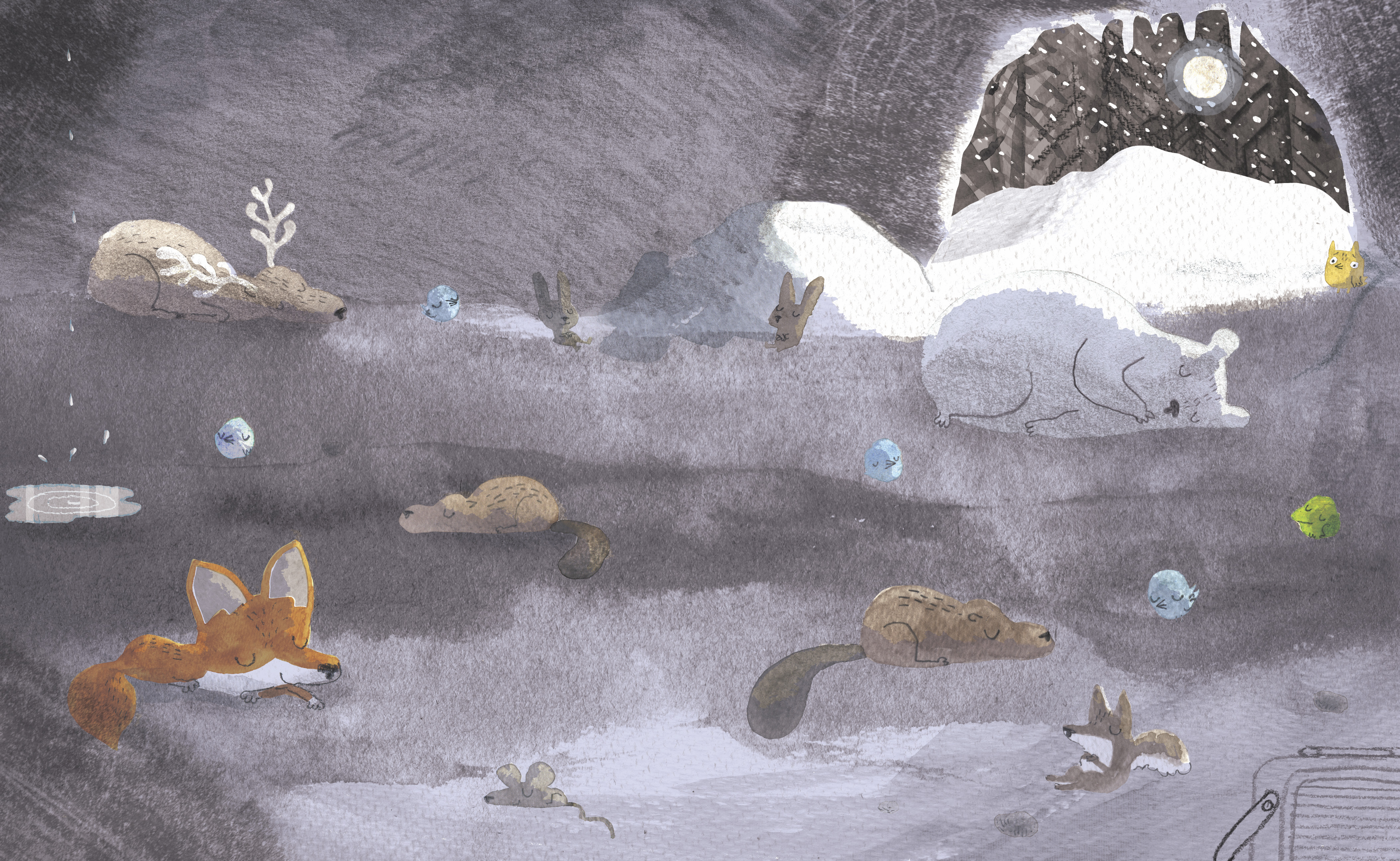

That was the idea, yeah. And they need to kind of replace that, and now they're just hungry to hear other things. But I wasn't quite sure at first where to go from here. I had a sketch at one point of a human, sort of explorer-type person who finds the radio and puts some new batteries in it. And I'm not sure why I thought that would be a good thing. That idea didn't last long.

I really liked the idea of the fox meeting the wind, and it's like the wind's kind of got personality. But when you work on a book, it's always a collaboration with the editor and the art director, and you just kind of hammer away at the story.

And the scene with the wind, we eventually decided, once the radio has died, let's have literally just the sounds that we would hear or animals would hear.

There was also going to be this big collective ending, with everyone sort of playing like bits of tree trunk and stuff like that.

You can see from that sketch, it's just hard to kind of get that scene together convincingly anyway. Because it was like, yeah, what are they gonna do? Like the woodpeckers are going to tap out a rhythm, and then the animals are going to be in a big orchestra or band or something? It just didn't seem necessary.

We decided that we should not make it fantastical or supernatural. Because part of our thinking was that sound really helps you to be in the moment. So you can hear the wind or hear water dripping from melting ice and it's meditative, isn't it? So we wanted to go more in that route, and the idea of this big wind character and a whole animal orchestra didn't fit in with that.

In terms of this meditative quality of sound, do you think that we're sort of oversaturated right now, culturally or sonically?

Yeah, we are completely oversaturated.

I was at a publisher today and we were just chatting about stuff, and we were talking about how the danger now for kids is that there's so much to draw them away from the simplicity of just reading words on a page.

And it's the same with sound. You know, when we were kids you couldn't think of a song and think, "I'm gonna listen to that right now" unless you had the CD. Now, kids can just, like, listen to anything.

And I don't know if that's bad. Possibly it's detrimental in some way, but then, some of my creativity comes from when I was a kid sitting in front of the TV a lot, you know? I don't know if it is good or bad, but it's a lot, isn't it?

And so this story kind of evolved. It went from appreciating sounds and then creating them into the idea of just being in the moment. The way that just listening can be a mental cleansing sort of thing, you know?

Ged Adamson is an author and illustrator based in London. You can follow him on Instagram or at his website.