I started grad school in August 2005, the same month that Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. I was in an American Studies program, so watching the disaster and its aftermath play out in popular culture felt historically significant. It wasn't every day that one of our country's most popular rappers declared that the president didn't care about black people on national television, with that same president making a speech a week later to acknowledge that "poverty has roots in a history of racial discrimination, which cut off generations from the opportunity of America."

It felt like a particularly American event, and it's one that has stayed with me for years. One of my professors at Iowa was already studying the history of disasters; he incorporated Katrina into his courses, including the Intro to American Studies class that I would TA for and teach over the next several years. My students and I watched Spike Lee's When the Levees Broke; compared the federal response to Katrina with what happened in the Mississippi Flood of 1927 and Hurricane Betsy in 1965; debated the meaning of the word "refugee"; speculated on what makes a disaster "natural" and what makes it decidedly human.

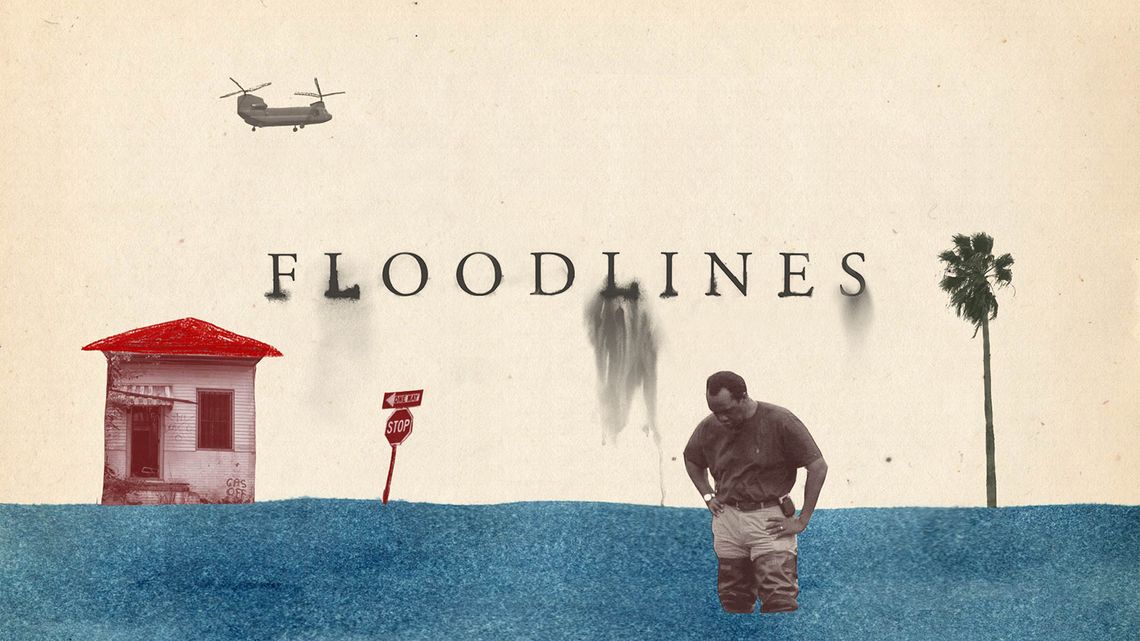

So when I finally listened to Floodlines, a podcast series from The Atlantic released earlier this year about Katrina, I was already pretty familiar with the story. In fact, some of the narrative beats it takes (and even some of the people that are interviewed) are lifted directly from When the Levees Broke, which remains the definitive documentary account of the tragedy. But revisiting Katrina as a podcast in 2020, in the light of nationwide protests about racism and racial equity, made me realize how important it is to tell this story again—right now—to remind people just how dangerous mainstream narratives about Black Americans can be. Why, some 15 years after an entire city was left to fend for itself in the wake of a very bad storm, does the news media still insists on covering social justice issues by talking about property damage and petty theft?

As a quick refresher, the "disaster" of Hurricane Katrina was not the hurricane. While there was fear at one point that it would make landfall as a Category 5 storm, it actually came in as a Category 3 and veered north of city. The flooding that followed was caused by failures in the levees that surround the city. That was an engineering probem. But as the water rose, deeper and more sinister issues came to the surface. With almost all power and telecommunications cut off, residents were forced to rely on radio and face-to-face communication to figure how and where to get help. People were going to the Superdome, to the convention center, or sheltering in place. But no matter where they went, basic supplies like food and water were largely unavailable.

With the federal response virtually nonexistent for days, the news media focused relentlessly and almost exclusively on stories of looting, property damage, violence, and rape—including stories about the rape of young children. By ignoring the larger issues and focusing on alleged acts of human depravity, the media actively made the problem worse. Humanitarian groups like the Red Cross further delayed their relief efforts based on the belief that the city was unsafe to enter.

But here's the thing: those stories simply weren't true. Some were based on unsubstantiated rumors, while others were demonstrably false. There were "reports" that groups of armed men were shooting at rescue helicopters—yet no helicopters came back with bullet holes. There were "reports" that widespread gun violence, murder, and sexual assault was happening at the places of refuge—but in later accounting, very few such incidents were verified. In fact, people sheltering at the convention center said that they felt the most threatened by National Guardsmen, who were position on the upper levels of the building like snipers.

This disconnect between the national news narrative and the account of people on the ground is where Floodlines and its narrator, Vann R. Newkirk II, are at their best. The series as a whole focuses on everyday people who survived Katrina and its aftermath, giving us their perspectives on the storm and how it has impacted their lives since. By structuring the podcast around these individual narratives, Floodlines does the work that other media outlets refused to: actually listening to the city's residents and treating them as complex, thoughtful people. And in doing so, the show exposes just how toxic the narrative around Black violence and property destruction is in this country. At one point, reflecting on the portrayal of Black New Orleanians as violent "animals," or "the worst of humanity," the podcast asks us to consider not only why these stories were reported, but why anyone, journalist or otherwise, would believe them. This is racism laid most bare: the belief that some people are less than human.

Part of the reason Floodlines is so effective is that Vann Newkirk does such a wonderful job taking us through the story. The show is extremely well written, which is to say that it feels written, in a good way. This is not someone pretending to be your friend and letting you in on a little secret, nor is it someone pretending not to know the beats in their own story and feigning surprise at every turn. As a listener, I'm so fatigued by both of those modes that it felt downright refreshing to hear someone who was obviously reading well-written lines.

Here in 2020, it's alarming and saddening if not completely surprising to see that the issues Hurricane Katrina laid bare are back: how the federal government treats Black Americans; how private property is valued over human life; how white Americans view people of color crying out for help. The difference, of course, is that our current disasters cannot be blamed on a weather system.

So go listen to Floodlines and let me know what you think.