COVID-19 has fundamentally restructured our daily lives, and the sounds of our communities right now reflect that fact. In some places, it is much quieter than it has been in a long time—both audibly and seismically. And while there might not be dolphins swimming in the Venice canals, the oceans are noticeably quieter. The world is slowing down.

It’s tempting to see this as a good thing. In the relatively low-key world of field recording listservs and Facebook groups, this was—at least initially—practically a cause for celebration. Some early posts expressed what could almost be described as glee. Excitement was bubbling to the surface about getting recordings never before possible, documenting nature in the metropolis, capturing this moment of nearly unimaginable change.

That sense was soon tempered by the awareness that such change was only possible because of human death. One email from a listserv member in Paris was filled with grief and anger. It was a gut-check, and a much-needed reminder that fantasies of ecological purity often come from a specific place of privilege: those not affected by the human cost that such a fantasy would require.

Fetishizing this kind of “silence” is reminiscent of William Cronon’s critique of an environmentalism that was obsessed with “wilderness,” places that acted as the opposite of human culture. Believing in that formulation, he writes, “is to take to a logical extreme the paradox that was built into wilderness from the beginning: if nature dies because we enter it, then the only way to save nature is to kill ourselves.” Or, in this case, have a virus do that part for us.

But like so many things that happen on a global scale, the scale itself is extremely important. Locally, some people might be experiencing a much louder environment than usual. One of those people is music critic Lindsay Zoladz, who recently wrote about living by a hospital in Brooklyn. Though she lived there for years, she only recently became so acutely aware of it. The sirens make it seem like “around the clock, the city itself were were wailing for its sick and dying.” Just across town, one person’s silence is another person’s pain.

Zoladz uses the work of composer Pauline Oliveros to help process this experience. Oliveros spent a large portion of her life exploring the notion of “deep listening,” initially an improvisational artistic practice that evolved into a definition of the difference between hearing and listening. Oliveros explains it here:

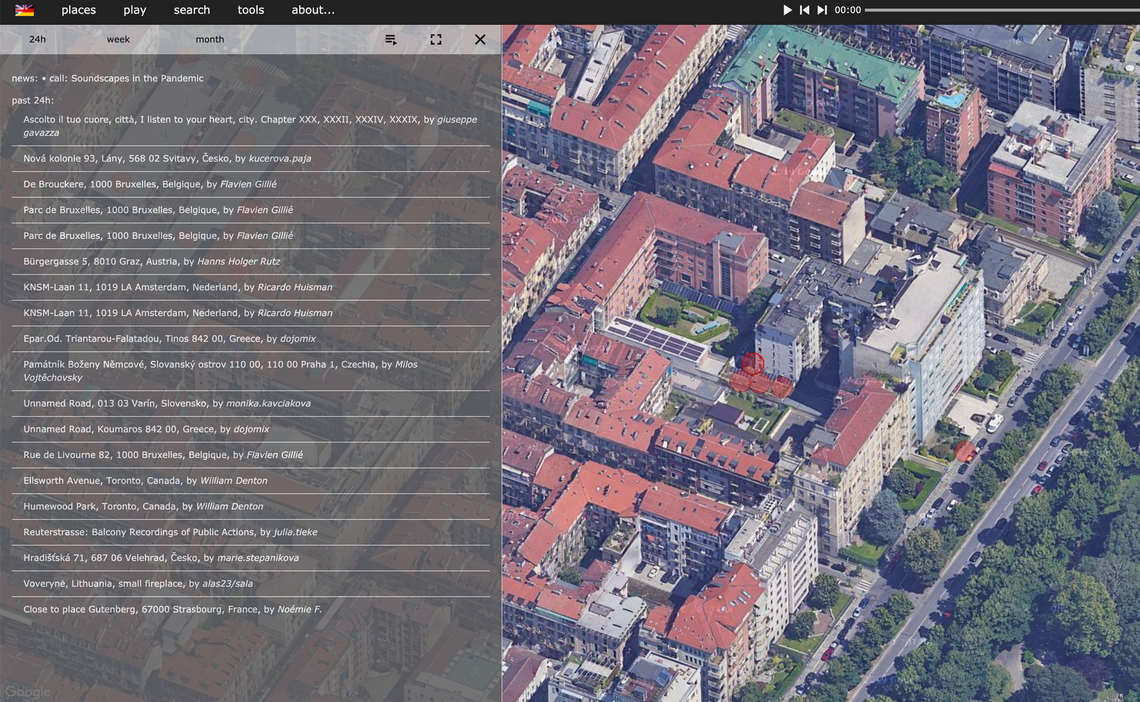

Both the work of deep listening and the process of understanding COVID-19 are intensely linked to physical places. So it makes sense that one of the primary ways people are trying to understand both has been to use maps. Like many news sources, the landing page for the New York Times coverage of COVID once prominently featured their map, and several soundscape mapping initiatives have come across my desk in the last week or two (see here, here, and here, also linked below).

Of course, this raises its own issues, on both a small and large scale. For starters, COVID maps focus on geographic borders, but we know the virus spread in part through airline travel. Secondly, well, all maps are wrong.

Nevertheless, COVID-19 sound maps do seem to have the potential to tell us something, both now and in the future. For starters, they can give us a hyperlocal perspective in a global crisis. Sound maps give us the ability to record both “sonic trophies” for experienced sound hunters (a rare bird in an urban environment, or whatever) as well as the everyday experiences of pain and suffering that are very much being experienced on the ground. They also present an opportunity not to fetishize quietude, but to reflect on what noises we’ve become accustomed to, especially in urban environments. And they also allow us to track changes over time, since recordings are usually datestamped. And, like any archive, the current “usefulness” of this data isn’t always the point. It’s use, or significance, might only be clear to us years from now, and there is something to be said for the collection of sounds as such.

(And yet, I can’t help wondering if these maps are more or less “effective” than narrative projects with very little “data,” such as Erica Heilman’s “Our Show” series?)

In other words, sound maps might help us answer this question: when life returns to “normal,” should the noise come back with it? Or can we imagine an alternate future that involves a more humane and balanced relationship between the noises of urban life and the noises of the nonhuman world?

All of these mapping projects allow for contributions, so you can not only listen, but actively submit your own soundscapes. In that way, maybe some more of us can participate in trying to create a representative soundscape of our moment.

- #StayHomeSounds, from the Cities and Memory Project

- A COVID-19 sound map on Google Earth by Pete Stollery (seems to be mostly focused on the UK at the moment)

- Corona Project Map, a subset of the long-running Radio Aporee general sound map

As always, thanks for listening. Feel free to share any thoughts you have about your COVID soundcape with me over email or in the comments. Talk to you soon!